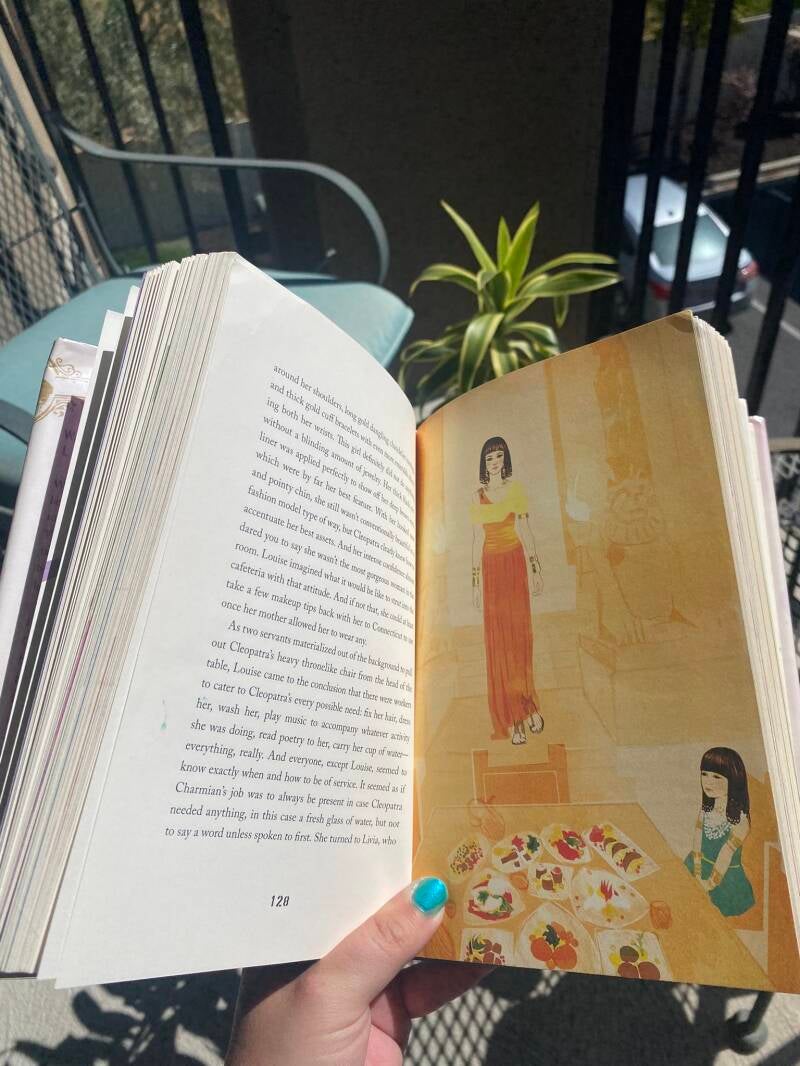

A few weeks back, I discovered this cute (and gorgeously illustrated) YA series called The Time Traveling Fashionista. The reader follows twelve-year-old Louise as she tries on vintage dresses that transport her back to the voyage of the Titanic, the court of Versailles, and Cleopatra’s Egypt. I wished I would’ve discovered this series back in the 2010s, when I was in middle school. There has long been a shortage of YA protagonists on the younger age of the teen spectrum. Recent headlines have noted that YA is getting progressively older—90% of teen characters in bestselling books are in the upper high school age bracket.

If you’re a reader in your early teens, this leaves you without characters in your same stage of life.

I’ve often been told to make my teen characters older on the grounds that a thirteen-year-old will read about a seventeen-year-old but older teens will not read about younger teens. Yet here I am as a twenty-eight-year-old woman loving a book series starring twelve-year-old Louise. There is no reason that older people can’t enjoy stories starring younger protagonists. The writing world often talks about relatability and the concern that kids won’t read if they can’t find books with characters like themselves. If a thirteen-year-old doesn’t like to read at that age, they may never become a seventeen-year-old who likes to read. I suspect the inclination towards older protagonists is more about giving adults a character they can relate to rather than giving younger teens characters they will look up to.

YA’s tendency to revolve around older characters seems geared towards giving them more freedom and ability to do grown-up things. A few years back, I gave my writing group a story about a twelve-year-old empress ruling an empire with an iron fist. They didn’t feel it was realistic. When I had a seventeen-year-old queen conquering a country in the same story, they were okay with it. It’s not very realistic for a seventeen-year-old to conquer a country either, but we let older characters get away with it. In short, YA is full of older teen characters who act like adults instead of teenagers.

One inherent problem with young adult literature is that most of the people involved in the book world are adults. I wrote YA from age 15 but wasn’t ready to publish yet. Editors, agents, and other publishing professionals are adults, as are the librarians and booksellers. Though social media is a huge part of teen life, most of the people generating hype around popular books are adults. When I was a teenager, I wrote a five-star review of a book I loved and then sent the author a link to the review. She replied saying she was happy I enjoyed it because “it’s not often that I get a review from a real teenager.”

It’s great that older people want to read YA, but all that involvement from adults creates a space where children’s books inevitably become what adults want to read (or what adults themselves think children ought to read) rather than books that suit a younger person’s tastes. Both the adults who attempt to ban or restrict access to YA books AND the adults who insist that teenagers benefit from reading mature content project their views and values on younger people.

One thing I really love about the Time Traveling Fashionista is how youth-friendly it is. The illustrations make the book engaging for preteen readers (and older ones like me!) and romance takes an age-appropriate backseat role. A few weeks back, my friend and fellow writer, Tanner Millett, volunteered at a writing conference where he told another author that his work-in-progress didn’t have a romantic plotline. The young hero would set out on an adventure by himself and then return home to be with his hometown sweetheart at the end. After being encouraged to change the book so that the hero went on an adventure with a girl at his side, Tanner concluded that adult women who read and write YA expect romantic subplots. He has written extensively on the gendered aspects of that topic here.

I think it’s also worth noting that the expectation for teenage characters to be involved in a romantic relationship is probably informed by age as much as it is by gender. When I was a teenager, my most important relationships were with my friends and family, not the cute boy in math class. When you’re fifteen, you know you’re probably not going to marry your school crush. Meanwhile, you want your friendships and family relationships to be strong forever. The average teenager feels more anguish over “my parents are getting a divorce” or “my best friend and I are fighting” than “the cute boy at school didn’t text me back.” While romance is popular in a lot of media marketed towards teens, it’s not terribly important in real teen life.

This past weekend, I invited a friend over to watch the book-based movie Aquamarine because it features mermaids, like the book I’m currently writing. One thing I remember loving as a teen was that all the lead actresses in Aquamarine were actually teenagers in contrast to the usual twenty-five-year-old actors you see pretending to be high schoolers. The two human main characters were fifteen at the time the movie released and mermaid Aquamarine was eighteen. The core conflict revolves around two young girls coming to terms with the fact that one of them is moving at the end of the summer, putting an end to their best friendship. The slightly-older mermaid’s romance with a slightly-older lifeguard is a significant part of the story, but it still speaks to the interests and concerns of younger audiences.

When I was in my early teens, I enjoyed plenty of books with older characters and romantic plotlines, but I always felt a lack. I wished there could be more characters concerned with the types of things I was focused on in my teen life. The book I am currently working on includes notes of potential romance, but the primary focus is on a teenage girl’s rocky relationship with her mother. Adults who write YA have a responsibility to tell stories that resonate with actual teenagers, the people YA is ostensibly “for,” rather than the older folks who are increasingly crowding out what is supposed to be a teen space.

Add comment

Comments